We are currently living in highly tumultuous times. Change is in the air—and while some of it is scary, leaving us uncertain about the future, a lot of it is extremely necessary, and has been a long time coming. People are rising up and speaking out for injustices that have gone on for far too long.

Within the witchcraft/Pagan community, and within many of my social circles in general, there has been a lot of personal and collective shadow work being done surrounding issues of race, white privilege, and the fact that “the way we have always done things” isn’t working, isn’t good enough.

The fact of the matter is, all of us have to do better. Especially those of us who are not POC, and who have had the privilege of never being judged based on our cultures or the colour of our skin. We have a responsibility to listen to and learn from those who have experienced such racial injustices, and who suffer the most as a result of our failed social and political systems. We have a responsibility to learn about our histories, particularly our white colonial histories, and to understand how events that happened hundreds of years ago have an ongoing and lasting impact on the present. We have a responsibility to challenge outdated “social norms” and speak out against racism and white privilege.

Canada Day 153

With everything going on in the United States right now, and the country’s horrendously inadequate government, I find myself joining in with the many choruses of “man, I am so glad we don’t live there.”

And it’s true—I do consider myself very lucky to live in Canada, and not just because we don’t have an irresponsible Oompa Loompa as our President. Besides the brutal winters, Canada is overall a pretty great place to live—we’ve got universal healthcare, relatively low crime rates, decent employment rates, and pretty solid social welfare systems.

However, that said, I also recognize that I have had a very particular kind of experience within my country because I am a young, white, cis gendered, middle class woman. I have never experienced prejudice based on the colour of my skin. I’ve never encountered police brutality, or had any issues with the judicial system. I’ve never known what it’s like to lose a family member or friend because of racial injustices or the inadequacy of our law enforcement services. In essence, I’ve never known what it’s like to be on the other side of white privilege.

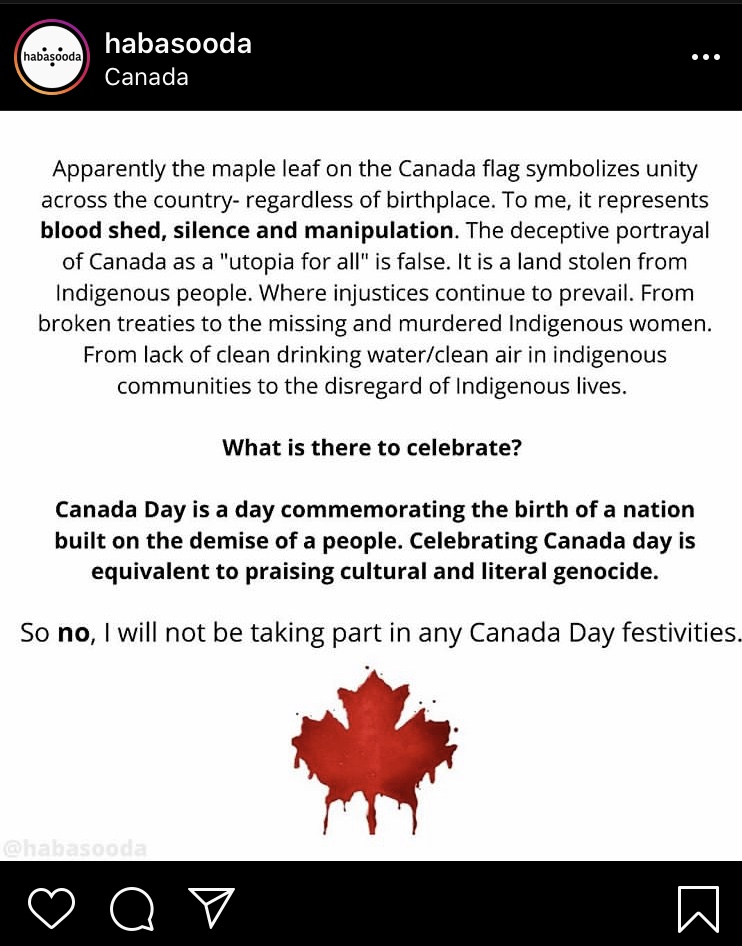

Yesterday (this post was meant to be up yesterday on the 1st, but I was experiencing major technical difficulties with this site!) marked the 153rd celebration of Canada Day, where we celebrate our nation’s independence with fireworks, beer, and free concerts (although much of this was canceled this year due to the ongoing pandemic). For many Canadians, it’s a joyous day of revelry and good times—and an excuse to get drunk and light things on fire.

But for others living in this country, Canada Day is not an occasion of celebration and fun, but of sorrow and mourning. For Canada’s Indigenous peoples, the day serves as a reminder of the horrors of colonial violence—of the lives lost, the families torn apart, and what can only be referred to as the cultural genocide that occurred as European settlers laid claim to these lands.

In Vancouver, BC, yesterday Indigenous people and allies held peaceful protests and marched for the cancelation of Canada Day. Led by the Indigenous activist group Idle No More, the march was held to honour the thousands of lives lost to the nation’s colonial history, and to protest the racism, white supremacy, and genocide that this country is ultimately founded upon.

While my own Canada Day celebrations consisted primarily of playing Animal Crossing and writing this post, I think that with both the pandemic keeping many of us at home this year, and the revolutionary attitudes rippling across the globe, this presents a critical opportunity for us to stop and think about how and where we might do better as Canadians.

And this doesn’t just apply to Canadians either–The United States have an equally oppressive and bloody history when it comes to the way colonizers treated Indigenous peoples, and the racial injustices they continue to face to this day. With the 4th of July coming up soon, this is also an opportunity for Americans to consider where they might to better as well. Just Like Canada Day, Independence Day is not a joyous occasion of celebration for everyone.

The Native Apocalypse

Over the course of the past few months, a primary focus in my studies and ongoing research has been Indigenous Studies, specifically Indigenous literatures. One concept in particular that stands out to me is that of the “Native Apocalypse”—a crisis that is not in some far-off future, but one something that has already happened, and that in many ways, continues on into the present.

Grace Dillon (Anishinaabe), writes about the concept of the Indigenous Apocalypse in relation to Indigenous Futurisms and Science Fiction, which maintain some of the tropes of Western sci-fi and futuristic fiction while escaping settler colonial bounds of the genre. She explains that while Western notions of the apocalypse see it as something that may happen in the imagined future, the “Native Apocalypse” is something that has already happened many times over in a very real past.

For Indigenous peoples, the apocalypse began with first settler contact, and the forced removal of Indigenous peoples from their home lands, continuing on with the mass spreading of diseases, as well as the cultural genocide that occurred through residential schools, where Indigenous children were removed from their families and forbidden from engaging in their cultural traditions or speaking their languages in the name of “assimilation”. Though we sometimes see these atrocities as having taken place in the distant past, it is important to remember that the last residential school in Canada closed in 1996—less than 25 years ago. Moreover, in the 1960s, what is known as the “sixties scoop” occurred, where Indigenous children were removed en-mass from their families, and moved into the welfare system, usually without consent.

The effects of this history of racism and oppression are still apparent within many Indigenous communities today, as intergenerational trauma continues to have a lasting impact on Indigenous families and individuals.

Here are some of the ways in which this intergenerational trauma can be seen:

- Indigenous families have higher rates of domestic violence and abuse than non-Indigenous Canadians

- 57% of First Nations children in Canada live in low-income families, and 35% of Indigenous children live with a single parent

- Indigenous peoples have considerably poorer health than non-Indigenous people, with higher risk for illness and early death

- Indigenous people in Canada generally have lower levels of education, with 34% having no high school certification (or equivalent), compared to 18% of the rest of the population

- There is a 25% income gap between Indigenous individuals and the rest of the Canadian population, and First Nations youth are twice as likely to be unemployed as non-Indigenous youth

- Indigenous peoples face higher levels of incarceration, making up 26% of all prison admissions, while only representing 3% of the total Canadian adult population

- There is a huge problem with Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) in Canada, with Indigenous women making up 10% of the total missing women in Canada

- Between 1980 and 2014, there were 6, 849 police-reported cases of female homicide victims in Canada, 16% of which were Indigenous. Since the early 1990s, the number of non-Indigenous female homicides have been declining, while it remains the same for Indigenous women

(Sources: The Canadian Encyclopedia, Indigenous Corporate Training Inc., JustFacts: Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls)

With all of this in mind, it shouldn’t be surprising to anyone that Canada Day isn’t an occasion for celebration for many Indigenous peoples across the country.

Racial Issues & Contemporary Spirituality

Over the past few weeks, I have seen that in general, the contemporary spiritual communities that I relate to and associate with have been doing excellent work in standing with BLM, speaking out against racial injustices, and examining their own circumstances of white privilege.

However, that said, there is always room for improvement, and areas in which we are lacking. Having seriously looked at my own actions, my own ingrained thought patterns, and my own complacency in oppressive social and political systems, I know that I certainly still have much to learn, and considerable work to do, as the progression towards genuine change is ongoing and everlasting.

Part of this change requires that we look at our spiritual communities, traditions, practices and beliefs themselves in order to determine where they fall short, and where they may in fact be perpetuating systems of oppression.

For all the wonderful work being done around these issues of race and white privilege among practitioners of contemporary spirituality and witchcraft, I have also noticed some people using their spirituality as a kind of excuse to escape from difficult conversations, or from facing the harsh truths of our societal situation. I’m referring here to issues of “spiritual bypassing,” wherein people attempt to sidestep real and critical issues by claiming that they are too “empathetic” to deal with them, or attempting to cover up real and pressing issues with band-aid-like blessings of “love and light.” Unsurprisingly, I’ve noticed that these people often tend to be the same individuals who say things like “all lives matter,” claiming that we should only be focusing on peace and love right now.

Of course, peace and love are among the ultimate goals, and it isn’t necessarily wrong to want to work towards them. The thing is though, we’ll never get to peace and love, or genuine equality of any sort without facing our individual and collective shadows, and owning up to difficult truths. Peace is ultimately unattainable without major change—without revolution.

This is partially why I tend to steer clear of anyone who refers to themselves as a “light worker”—transformation and wholeness can only truly come from embracing both the light and the shadow.

As part of taking a critical look at my participation in various Pagan and witchy groups (both online and offline), I’ve come to realize that the majority of these communities are predominantly white. Why is this, exactly? Is it because despite claims to diversity, Paganism nonetheless appears to be a form of “spirituality for white people”? If so, what can we as Pagans and witches do to make the community feel more open and welcoming to people of all colours, ethnicities, genders, sexualities, etc.? How can we do better?

I’ve also noticed that most of the Pagan and witchy YouTubers, bloggers, Instagram influencers, authors, etc. that I follow and support are white. I do see this as being an issue, and I am grateful to people like Kelly Ann Maddox who have been giving shout-outs and providing connections to wonderful black/POC witchy and spiritual content creators over the past few weeks. I think it is really important for us to learn from and engage with a variety of different voices, particularly if, like me, you may have found yourself stuck in the “white bubble” that seems to come along with much of contemporary spirituality and witchcraft.

“Plastic Shamanism” & Cultural Appropriation

My introduction to Paganism and witchcraft actually began with an academic interest in cultural/spiritual appropriation. During my undergrad and Masters in Anthropology, I centred much of my research around “plastic shamanism” and New Age appropriation of Indigenous traditions and practices.

“Plastic shamanism” or “white shamanism” basically refers to Westerners who learn about Indigenous shamanic practices of healing and spirituality, and then go on to sell their (often quite expensive) shamanic services to other Westerners, profiting off of stolen Indigenous traditions. This phenomena is also associated with “spiritual tourism,” as well as the romanticization and objectification of the native “Other” that it entails.

“Shaman” is a fraught term, its meaning having been contested among scholars for decades. Though the concept of the shaman originated in Eastern Siberia, it is now applied to hundreds, even thousands of religions world-wide. Though some scholars advocate for a broad definition of shamanism in order to account for this spread, others believe that it is best kept to the original contexts.

Most, however, agree that shamanism is not a religion as such, but a system of beliefs, rituals, practices and myths with multiple characteristics that span across time and space. Some of the defining features of shamanism include vision quests, ecstatic trances, and taking on the role of being an intermediary between this world and the spiritual otherworld.

Mircea Eliade, whose book Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy remains one of the most influential reference points for shamanism, defines it as “techniques of ecstasy,” making out shamanism to be a practice that can be applied universally to different cultures, rather than something that is culture-specific. Though Eliade has been criticized for taking an overly romanticized view of shamans as “exotic Others,” his understanding of it laid the foundations for Western “neo-shamanism.”

Along with Eliade, anthropologists like Carlos Castaneda and Michael Harner are credited with bringing shamanism to the Western world. Though Harner studied the Jivaro of the Ecuadorian Amazon for many years, he shifted the focus of his work to take up the path of the shaman himself, and in 1979 opened the Foundation for Shamanic Studies, where he led many workshops teaching people how to become shamans themselves. Harner developed the idea of “core shamanism,” which posits that if shamanism is stripped of its cultural elements, what remains is a core set of practices or techniques that can be learned by anyone. Since then, many more workshops, books, courses, and products have emerged claiming to teach westerners how to practice shamanism, and incorporate it into their own spiritual practices.

It’s not surprising, however, that this stripped-down form of neo-shamanism has received considerable critique, as it is based on a romanticized notion of shamanism that differs significantly from traditional practices, giving rise to a homogenized and distorted version of the Indigenous traditions it borrows from. Moreover, contemporary neo-shamanism is widely apprehended by members of the communities it takes these traditions from, as it undermines Indigenous integrity and values.

Contemporary neo-shamanism is often lumped in with New Age practices, and, unfortunately, with Paganism and witchcraft as well. Some beginner witchcraft books equate witchcraft with shamanism, claiming that one is a subset of the other. This I think is vastly misleading, as witchcraft is not the same as shamanism by any means, and the two are often very distinct practices. Moreover, these books never (or very rarely) go into the historical or cultural background of shamanism, completely disregarding the traditions and peoples it is associated with.

My own views on neo-shamanism and its prevalence within contemporary spirituality are rather conflicted and complex. On the one hand, the techniques of shamanism have been known to be spiritually beneficial and highly transformative for many contemporary western practitioners, and may serve to help people connect with their inner selves and work towards genuine change. However, while white practitioners may find empowerment in shamanistic practices, I have to wonder whether they understand its cultural and historical implications, and whether they recognize that the utilization of these practices are often cases of spiritual appropriation. I wonder how cognisant people are of the fact that spiritual/cultural appropriation can be harmful to Indigenous peoples and their traditions, and that in using some of these shamanistic techniques, they may be denying Indigenous communities sovereignty and integrity.

As such, I’m highly suspicious of white people who call themselves “shamans,” and even more suspicious of those who sell their services, profiting off of this spiritual and cultural theft.

Paganism, New Age & Spiritual Appropriation

New Age practices and products are undoubtedly complicit in issues of cultural appropriation, particularly with regards to the Indigenous peoples of North America. And as much as I hate to admit it, there is some overlap between New Age and contemporary Paganism and witchcraft that cannot simply be overlooked. It was actually through my academic interest in this “spiritual theft” among New Agers that I was first introduced to Paganism, as both practices involve considerable cultural syncretism and “borrowing.”

Pagans today generally draw from a range of ancient and modern belief systems, including (but certainly not limited to) Norse mythology, Celtic Druidry, occult mysteries, Egyptian religions, etc. For the most part, I think this remains largely unproblematic, as many of the traditions contemporary Paganism pulls from are no longer “living” traditions.

When things do become problematic, however, is when Pagans and other practitioners of contemporary spirituality start to draw from practices/systems of belief that are living and closed—such as those of the Indigenous peoples of Canada. Taking from living Indigenous traditions is not just spiritual “borrowing,” it is spiritual and cultural theft.

Michael York, who has written extensively on both New Age practices and contemporary Paganism states that not only does this spiritual exploitation “encourage a paradoxical homogenizing of the cultural standards of North Atlantic civilization, […] but it also carries an implicit judgement of the inferior status for non-hegemonic cultures, inasmuch as they are not considered to be the ones who decide what is to be shared and what is not” (2001, 368).

Cultural appropriation, in other words, denies Indigenous peoples the right to decide which aspects of their traditions they want to share with the world and which they want to keep to themselves. In essence, it denies them their sovereignty.

Earlier this year, I read Cherie Dimaline’s (Metis) YA novel The Marrow Thieves, which I think sheds an interesting light on this notion of spiritual appropriation. The novel is set in a not-so-far-off dystopian future, where climate change has destroyed much of the planet, and the dire situation has left many people without the ability to dream. The only ones who are able to dream (it is suggested, because of their lasting connection to the land), are the nation’s Indigenous peoples. When it is discovered that these dreams can be extracted from the bone marrow of the First Nations population, and transferred to non-Indigenous people, a widespread hunt for Indigenous people begins, resulting in many deaths, and leaving the survivors running for their lives in order to protect themselves and keep their cultures alive—a plot that serves as a reflection and reminder of Canada’s history of colonial violence.

In explaining the series of events that led to the hunting down of Indigenous peoples, the character Miigwans says:

At first, people turned to Indigenous people the way the New Agers had, all reverence and curiosity, looking for ways we could help guide them. They asked to come to ceremony. They humbled themselves when we refused. And then they changed on us, like the New Agers, looking for ways they could take what we had and administer it themselves. How could they best appropriate the uncanny ability we kept to dream? How could they make ceremony better, more efficient, more economical?”

The Marrow Thieves, p. 88

Here, the imagined theft of Indigenous abilities to dream, and eventually the appropriation of Indigenous bodies is equated with the very real New Age appropriation of spiritual practices. This includes the appropriation of things like sage smudging, the use of medicine wheels, working with totem animals, buying mass-produced dream catchers, and using sweat-lodges for ceremony and healing.

The big problem is that these spiritual practitioners turn to Indigenous practices for help in reconnecting with themselves and with the earth, yet do so without any genuine willingness to acknowledge or understand the struggles that First Nations peoples have endured as they strive to maintain and uphold these traditions in the face of an oppressive dominant culture that constantly threatens to wipe them out. These New Agers—and yes, some Pagans—romanticize First Nations peoples, commodifying and distorting their cultures without regard for their endurance in the face of genocide, land struggles, residential schools, and everything else that contributes to the ongoing “Native Apocalypse.”

I strongly believe that as Pagans, as witches, as spiritual practitioners in any sense, we need to look critically at our own practices and ask: where do they come from? Am I engaging in acts of spiritual/cultural appropriation? And if I am, what can I do to remedy this?

Beyond Cultural Appropriation

As I have mentioned in some of my previous posts, contemporary Paganism is by no means congruous with a historical pagan past, and is constructed out of a variety of comparatively “modern” sources and influences.

As Bron Taylor and other Religious Studies scholars have noted, contemporary Paganism, particularly as it can be considered a form of “dark green religion,” was (and continues to be) influenced by American nature writing, and is in debt to authors such as Henry David Thoreau, Aldo Leopold, and John Muir.

Now, this is something that I’ve only recently learned, as some of my MA research has taken me in this direction—but much 19th century North American writing is wrapped up with racism and prejudice against Indigenous peoples, as well as perpetuating overly romanticized notions of Native peoples.

Henry David Thoreau (author of Walden), for instance, wrote about the Native Americans he encountered during his travels and time spent living in the “wilderness.” The picture he paints of them is that of a “primitive” people, who are at once looked down upon for their “savagery,” yet also admired for their closeness to nature. Like much of his writing, Thoreau’s approach to the Indigenous peoples of America is paradoxical, reflecting a romanticized desire to learn from them insofar as they represent for him a “pure” connection to nature, and a need to distance himself from them, as they cannot be considered part of “civilized” society. Moreover, Thoreau’s published works and unpublished notes demonstrate that he thought of Indigenous cultures in the United States as being static, fixed, and primitive, stuck in an “uncivilized” past from which they could only hope to escape by virtue of the white man’s aid.

John Muir is even worse. As one of the most influential naturalists/conservationists of all time, Muir has inspired many environmentalists and practitioners of nature-based spirituality alike. Though Muir claimed to be opposed to the oppression of Native Americans, and his attitudes towards them can be seen to evolve throughout the course of his life, his conservation philosophy and the romanticization of “pure” nature untouched by human beings contributed to the genocide and displacement of Miwuk Natives in Yosemite Valley, California. In the name of the “balance” of nature, Muir wrote about how Yosemite Valley should be preserved from all human activity—including that of the “dirty” and “lazy” Indigenous people who lived there. This, in part, resulted in their forced removal from their traditional lands, the destruction of their ways of life, and many deaths.

Unfortunately, this warped idea of conservation that Muir promoted, wherein people have no place in wilderness, was for too long incorporated into America’s policies regarding National Parks and contributed to the displacement of many Indigenous populations.

This idea of “pure” or “untouched” nature is of course a fallacy—a romanticized notion of the natural environment that may be used to discredit the claims of the people actually living there.

In a sense, this conservationalist notion of “pure nature” can be connected to the fallacy of terra nullius (meaning “nobody’s land”)—the (false) notion that Canada was empty or uninhabited at the time of European “discovery.” This, along with the idea that because many Indigenous people were nomadic at the time and therefore had no claim to the land, was used to dehumanize, discredit and exploit Indigenous peoples, and to justify settler seizures of their lands. The fact of the matter is, however, that Canada is a lot older than 153 years—we just don’t tend to widely recognize its pre-colonial history, as it is simply easier for us to ignore these injustices, to sweep the violence and oppression that this country was founded on under the rug.

With all of this in mind, I can’t help but wonder if the fact that many contemporary Pagans and other nature-based spiritual practitioners see the likes of Henry David Thoreau and John Muir as “spiritual gurus,” sometimes even going so far as to treat their writings as “sacred texts,” should be problematized.

Like many people who engage with nature-centered forms of spirituality, my own practice and beliefs have been influenced significantly by writers like Thoreau and Muir, their work playing a role in shaping how I perceive and engage with the environment. Now, knowing what I do about the attitudes of these authors towards Indigenous peoples, I must approach them with a significantly more critical eye, in much the same way that I continuously strive for self-reflexivity in relation to all of spiritual beliefs, practices, and foundations.

As a part of this self-reflexivity, I think it is also crucial for me as a nature-based Pagan, whose spirituality is founded largely on my relationships with the natural environment, to recognize that I am living on stolen land—specifically, on the unceded territories of the Algonquin Anishinaabe Nation. Indigenous peoples have strong kinship-based ties to the land—reciprocal relationships with the nonhuman world that form a core part of their spiritual beliefs and everyday lives. Colonialism, genocide, racism, and ongoing oppression forever changed Indigenous connections to the land, and through things like climate change, pollution, pipelines, and other harmful settler practices, we continue to threaten these sacred relationships.

It has been important for me to recognize that my own spiritual connection with the Canadian landscape comes out of and is a part of the oppression and attempted irradiation of Indigenous relationships with the land, both past and present.

Again, I ask: how can we do better? How can we reconcile these injustices, and move towards lasting and meaningful change?

Like many things, I think that the answer to this begins with a willingness to take a critical look at our own prejudices, patterns of thought (whether conscious or unconscious), and spiritual practices, asking ourselves where there might be problems, where we might be lacking when it comes to social justice and equality. It begins with holding ourselves and those we engage with accountable, owning up to our mistakes, and challenging “the way things have always been.”

Indigenous Survivance and Self-Determination

I just want to end this (rather long—oops!) post with a note on Indigenous resilience and survivance. Although colonialism and ongoing settler violence has dealt a tremendous blow to the Indigenous peoples of Canada, resulting in the significant loss of lives, of ways of life, and of languages, it is important to understand that these people and their cultures have NOT been lost completely. Again, it is a fallacy to conceptualize Canada’s Indigenous populations as “disappearing,” or as being stuck in the past, unable to find their place in modernity. Even though the Native Apocalypse has already happened (more than once), Indigenous peoples have always survived—in fact, they have more than survived.

Gerald Vizenor (Chippewa) uses the term “survivance” to describe Indigenous resilience in the face of oppression, a term that refers to “an active sense of presence over absence, deracination and oblivion” (85). Survivance goes beyond survival to connote active resistance to dominant power structures and the refusal to be mere victims.

As Leanne Simpson (Nishinaabe) notes, Indigenous resistance is not only about surviving past and present apocalypses, but also about being able to carry on into the future, and to be able to find cultural resurgence and flourishment despite all that they have suffered through. In order for this resurgence to become a widespread possibility, what they need from non-Indigenous people is not white saviours or pity. What they need is the space and freedom for their cultures to grow, and for sovereignty and self-determination to take hold.

In essence, we need to not just figure out who we are; we need to re-establish the processes by which we live who we are within the current context we find ourselves. We do not need funding to do this. We do not need a friendly colonial politics climate to do this. We do not need opportunity to do this. We need our Elders, our languages, and our lands, along with vision, intent, commitment, community, and ultimate action. We must move beyond resistance and survival, to flourishment and mino bimaadiziwin [living the good life].”

Leanne Simpson, Dancing on Our Turtle’s Back: Stories of Nishnaabeg Re-Creation, Resurgence and a New Emergence

Anyways, I apologize (again) for the really long post, but this is something that has been on my mind a lot, and a topic that I’ve been wanting to write about for quite some time. As always, thank you so much for reading, and if you have any thoughts or opinions on any of this, I would love to hear from you.

If you’re interested in donating in order to help Indigenous communities in Canada, one of the organizations I would recommend is The Native Women’s Association of Canada, who have done really critical work involving the epidemic of MMIWG, and are currently providing support to Indigenous communities who have been hit particularly hard by COVID-19. Though the cases of the illness have been on the decline in Canada, Indigenous communities have been disproportionately affected by it due to system inequities and discrimination, including poverty, lack of access to clean water, and higher rates of underlying health conditions. In recognition and support of Indigenous voices, I donated to this organization with the money that I would typically be spending on booze for Canada Day celebrations.

References

Bowie, Fiona. The Anthropology of Religion: An Introduction. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 2000.

Castaneda, Carlos. The Teachings of Don Juan: A Yaqui Way of Knowledge. Berkley: University of California Press. 1968.

Dillon, Grace L. “Imagining Indigenous Futurisms.” In Walking the Clouds: An Anthology of Indigenous Science Fiction, edited by Grace L. Dillon, University of Arizona Press, 2012, pp. 1-14.

Dimaline, Cherie. The Marrow Thieves. Cormorant Books Inc., 2017.

Eliade, Mircea. Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy. Princeton New Jersey: Princeton University Press. 1964.

Fleck, Richard. “John Muir’s Evolving Attitudes Towards Native American Cultures.” American Indian Quarterly, vol. 4, no. 1, 1978, pp. 19-31.

Harner, Michael. The Way of the Shaman: A Guide to Power and Healing. San Francisco: Harper & Row Publishers. 1980.

Maddox, Lucy. Removals: Nineteenth Century American Literature and the Politics of Indian Affairs. Oxford University Press, 1991.

Simpson, Leanne. Dancing on Our Turtle’s Back: Stories of Nishnaabeg Re-Creation, Resurgence and a New Emergence. Winnipeg: Arbeiter Ring Publishing. 2011.

Taylor, Bron. Dark Green Religion: Nature Spirituality and the Planetary Future. Berkeley: University of California Press. 2010.

Townsend, Joan B. “Individualist Religious Movements: Core and Neo-Shamanism.” Anthropology of Consciousness. 15(1). 1-9. 2005.

Vizenor, Gerald. Native Liberty: Natural Reason and Cultural Survivance. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009.

Wallis, Robert J. Shamans/Neo-Shamans: Ecstasy, Alternative Ideologies, and Contemporary Pagans. London: Routledge. 2003.

York, Michael. “New Age Commodification and Appropriation of Spirituality.” Journal of Contemporary Religion, 16(3), 361-372. 2001.

Indigenous novels and creative works I’d highly recommend checking out:

Cherie Dimaline’s novel Empire of Wild

Patti LaBoucane-Benson & Kelly Mellings’s The Outside Circle: A Graphic Novel

Tanya Tagaq’s Split Tooth (especially the audiobook version… also check out her throat singing!)

Waubgeshig Rice’s novel Moon of the Crusted Snow

Gwen Benaway’s collection of poetry, Holy Wild

Eden Robinson’s collection of short stories, Trap Lines

Thank you for this detailed essay about this issue. I’m currently in training with the Indigenous Relations Academy and I’ve read numerous comments from folks in the neo new age community about this topic. It seems as though some are becoming quite the fundamentalists about this. Sage, by itself as an herb, is not owned by any single group of peoples. Burning sage is also not owned by any group specifically. The practice of smudging is..with it’s combination of herbs that they use in specific ceremonies and practices. What are your thoughts on this?

Hi Lisa, thanks for your comment! You’re right, the topic of sage does seem to be a huge point of contention within Neo-Pagan and New Age communities these days. I agree that sage is not owned by any one group, and don’t necessarily think that burning sage is an issue. I think it becomes an issue when people attempt to appropriate particular smudging ceremonies, as these are closed practices.

I am Ojibway! How about Witches Against Colonialism? Witches Against Cultural Appropriation! New age light and love is the exact same of Jesus saves. The masses are easily fooled. They dupe on enlightenment is one of the biggest money making schemes.

Hey would you mind stating which blog platform you’re using?

I’m planning to start my own blog in the near future but I’m having a hard time

making a decision between BlogEngine/Wordpress/B2evolution and Drupal.

The reason I ask is because your layout seems different then most

blogs and I’m looking for something unique.

P.S Sorry for getting off-topic but I had to ask!

Hi there! I use WordPress–it’s the only platform I’ve ever used so I can’t really compare it to anything else, but I do like the many options for customization it allows. Best of luck with your blog!

This was an interesting article though I am not sure it was a useful article. It’s of the kind and quality that I would expect from someone studying anthropology. That is to say I enjoyed it for the most part.

I think my disappointment stems not from the content of the article but from what it did not contain. What cultural appropriation is was laid out masterfully. The explanation why modern paganism is not cultural appropriation was also done very well. As was the drawing attention to the problematic history of your own tradition. What is missing however is the conversation of adoption vs appropriation.

The difference as I understand it is that appropriation with incorporation of a foreign element without either acknowledging it’s origin, or in a way that undermines the original meaning of the element. Adoption on the other hand has gradation and seeks to incorporate a foreign element while acknowledging and reinforcing the link to the source, or by modifying the element so heavily that an outsider would recognize it as a new thing unless they had some kind of deep background or it was explicitly explained to them.

I have two grandmothers on both sides that were pagan. One had voodoo mixed it Catholicism and the other had Indigenous mixed in with Catholicism. Each had their unique way of practice and belief. They always used what was available in their environment to do magic and both new how to forage and grow gardens by the moon phases. One would use the tarot (playing cards) and the other had prophetic dreams could interpret dreams and both were healers. As you know they were only popular when the people needed help with something other than that they conversed together or were loners. They both knew magick came from within and didn’t have fancy items to do magick. They did not read books or watch movies and copy what was in these mediums. They had an innate knowledge of the world and tapped into its resources. Most stuff now comes from Hollywood, or people who want to make a buck or celebrities. Now days fake magick is for sale. One grandmother used sage and the other used grown herbs. In a Country of abundance, we seem to lack a spirituality, so we look to other places and practices even though they used to outlawed and now accepted by the colonist.