For our health, we have to preserve our physical world—the environment our bodies need to survive on this earth. But we also must preserve the environment our spirits need to survive in eternity. The tree is essential to one, and the symbol of the tree is essential to the other. The physical tree sustains our bodies with its fruit, its shade, its capacity to reproduce oxygen and to hold the fertile soil safe. The mythic tree sustains our spirit with its constant reminder that we need both the earth and the sunlight—the physical and the spiritual—for full and potent life.”

Moyra Caldecott, Myths of the Sacred Tree

In my last post, I explored how contemporary Paganism can be considered a form of nature-centred spirituality, wherein practitioners develop powerful relationships with the natural world—relationships that are typically not just one-sided, but rather, fundamentally reciprocal.

Many Pagans may foster special connections or kinship relations with specific elements of nature, such as a large rock in an overgrown garden that makes a perfect mediation spot, or a clearing in the woods that for whatever reason, feels especially sacred.

Indeed for some Pagans, such special bonds often formed especially with trees, as they are potent sacred symbols within many traditions. For some, trees may be seen as homes to fae creatures and other mythical beings, or may even be considered the resting places of earthly deities. Others may take a more naturalistic approach, appreciating the majesty and intrinsic value the forested landscape.

While personally, I love the legends and lore surrounding trees and mythical forests, I don’t necessarily believe in the literal existence of such spiritual/otherworldly beings. Instead, I find myself drawn to trees largely because of their physical presence—there’s just something about these magnificent plants that intrigues my soul and excites me spiritually.

For most of us, trees play a significant role in our daily lives, whether we’re conscious of it or not. They make up the bones of our houses, and the furniture that we fill them with. They provide us with nourishment and with clean air. They give us places to play, to hide, and to seek refuge. They are homes for countless other species, and a vital life force of this planet.

Trees are, quite simply, amazing.

Over the past few months, my growing fascination with trees means that I’ve come to see them as exceptionally powerful spiritual entities, both materially and symbolically.

With this in mind, there are four major areas I want to address in this post. First, I explore some of the benefits of nature in general, demonstrating how the natural world is intimately tied up with human well-being. Second, I look at the spiritual significance of the natural world—namely, trees and scared forests. In particular, I look at Irish Celtic (pre-Christian) paganism as an example of how spirituality and identity can be so closely bound up with the forested landscape. Next, I draw connections between Celtic relations to trees and my own engagement with them as a contemporary Pagan. Finally, I end this post with a brief look at Diana Beresford-Kroeger’s book To Speak for the Trees as a poignant example of how ancient spiritual wisdom and modern science can go hand-in-hand when it comes to how we interact with and perceive the natural world.

I know that this is A LOT to pack into a blog post, and that much of it likely won’t be of interest to everyone, so I do apologize for that! And, as with any post I write, I encourage you to skip to any sections that are most relevant to you!

Biophilia: Love of Life

Biophilia is a term popularized by Edward O. Wilson in 1984, literally meaning “love of life.” Wilson and others following him use the term to refer to our innate inclination as humans towards living things—basically, a biological drive to seek connection with the natural world. Although on average, we now spend 90% of our lives indoors, as a species, we humans spent over 95% of our evolutionary history immersed within and as a part of nature. As such, it makes sense that we have such an affinity for and innate attraction to the natural world.

As Paul Harrison points out, whenever we’re separate from nature, such as when we find ourselves living in big cities or “concrete jungles,” we often try to bring nature to us, recreating aspects of it around us. For Pagans and witches, this may mean filling our spaces with houseplants, crystals and other minerals, and images or works of art depicting natural elements.

In architecture and design, biophilic design is an intentional strategy that attempts to incorporate natural elements into our dwelling spaces in order to satisfy this drive towards nature. It stems from the understanding that we all have a deep fascination with natural forms, from patterns on leaves to the shape formed by clouds, or the outline of a mountain top against the clear sky.

One form in particular that we are especially drawn to, and that repeats constantly throughout nature, is what’s known as the “golden ration” (1:1.68). Found in the spiralling centre of a sunflower, the pattern of a snail shell, and the swirling of galaxies, this ratio is considered to be universally appealing, and has been the inspiration and basis for much art and architecture.

Nature and Wellbeing

For centuries, human beings have known about the healing powers of nature, and the incredible ability of the natural world to enhance mental and physical well-being. Now, through rigorous empirical study, scientists have been able to demonstrate that nature does indeed have a significant effect on human health and happiness. Over the past few decades, countless studies have been published connecting nature to physiological and psychological well-being, which, in turn, may also be connected to spiritual wellbeing.

Nature and Healing

In 1984, Roger Ulrich conducted a seminal study that looked at the relationship between nature and recovery among hospital patients who had just had surgery. This study has gone down in history as one of the first instances of concrete evidence for the biophilia effect, as it demonstrated that patients who had a view of nature and trees from their windows recovered, on average, significantly faster than those who didn’t have a window, and only had a view of the wall.

Since the 1980s, many scientists have used this research as a point of reference for their own work, and Ulrich’s findings have been confirmed many times over. It has since been discovered that even when patients encounter elements of nature through sounds, images, or videos, rather than through actual physical encounters with it, they are nonetheless still able to heal quicker than those who have not been exposed to such natural elements.

Studies have also shown that exposure to nature can help mitigate pain, by distracting patients, and directing their attention elsewhere. When patients have a view of nature from their rooms in hospitals, or are able to visit the hospital garden often, they require less pain medication (around 22% less) than those who don’t have this contact with nature. Additionally, a study by Sara Malenbaum et al. found that patients recovering in hospital rooms with more natural lighting also required less pain medication than those in darker, less well-lit rooms.

Nature, it seems, is quite literally a form of medicine.

There is only one healing power, and this is nature”

Arthur Schopenhauer

Nature and Stress

In addition to pain and healing, many studies in recent years have also found a strong correlation between natural environments/elements and a decrease in stress.

Stress is known to have many potential serious physical and mental effects, including anxiety, depression, and fatigue, as well as being linked to serious conditions such as heart/circulatory diseases and a weak immune system. Research shows however that in order to help mitigate some of these stress related issues, one need only go for a walk through a forest, spend some time in a park, or even do something as simple as look out the window for a few minutes.

In a Japanese study by Qi Ling and his team at the Nippon Medical School in Tokyo, it was discovered that spending a day in the forest can significantly reduce stress-related adrenaline hormones by around 30% for men, and 50% for women.

In another study by Juyoung Lee et al. on the practice of shinrin-yoku or “forest bathing” in Japan, it was found that people who took a walk through the forest had significantly lower heart rates, and reported better moods, increased relaxation, and less anxiety than those who walked through the city.

Interestingly, Bum-Jin Park et al. found that it is not only the observation of natural environments that can help us de-stress, but that the actual aromatic scents released by plants within natural areas play a significant role in lowering blood pressure. These scents and their effects can even be reproduced within the home to some extent by, for example, diffusing cedar or other tree oils in a room.

Nature, Creativity & Productivity

Within the past few decades, researchers have become increasingly interested in the effects of nature on human creativity and productivity. Studies such as those by Ruth Atchley et al. and Trine Plambech and Konijnendijk van den Bosch have found that spending time in nature can help boost productivity and enhance creative ways of thinking, particularly by “recharging” the mind, and making us more curious, flexible in our thought patterns, and open to new ideas.

Moreover, studies like that by Kate Lee et al. have found that just looking at nature, whether through a window, video, or even picture, can help increase our focus and make us more productive.

Whenever I’m feeling uninspired, or stuck in a creative rut, I often find that even just going for a short walk outside really helps me get back into my groove. In some ways, spending time in nature is like pressing a big reset button, helping you let go of whatever has been holding you back so that you may work instead towards being the best version of yourself.

Nature and Spirituality

So, with all this in mind, I think it’s pretty safe to say that nature is nothing short of fucking awesome. However, in addition to all the wonderful benefits nature can have for our health and wellbeing, as a nature-based spiritual practitioner, and as a “witchy” blogger, I’m also interested in the relationship between nature and spirituality.

While I was doing research for this post, I found that it was somewhat difficult to find empirical studies directly relating to this nature-spirituality connection. The reason for this, I believe, is because spirituality is not something that is easily measurable, and cannot necessarily be quantified in say, the same way something like blood pressure and stress hormones can be. There are of course plenty of personal narratives and accounts of spiritual connections with and transcendental moments within nature, but these kinds of experiences are notoriously difficult to even describe, let alone quantify.

In particular, I’m especially interested in the spiritual power of trees and forests, as these are elements of nature that have always held a special place in both my heart and imagination.

Of the studies pertaining to spirituality and nature that I did find, one that stands out in particular is that by Kathryn Williams and David Harvey looking at the types of transcendental and spiritual experiences that people have within forested areas. Interestingly, in a survey of over 100 people, they found not only that forests are positively correlated with transcendent, mystical, or otherwise spiritual experiences, but also that the nature and quality of these experiences change depending on the kind of forests people find themselves in. They found that in forests with grand features like roaring waterfalls and massive trees, people are more likely to experience sensations of awe and diminished sense of self, while in smaller, less sublime settings, they were more likely to experience feelings of interconnectedness and closeness with nature. This study therefore goes to show just how important our physical environments can be in catalyzing and constructing spiritual experience and meaning.

Sacred Trees and Forests

The sacred power of trees and forests can be seen in cultures across the globe, and often extends back thousands of years. In India, for instance, thousands of sacred trees are protected by rural communities, as they are often believed to be homes for local gods and ancestral spirits. The gods and spirit guardians associated with these such trees are generally considered to be specific, place-based spirits directly tied to the land and its trees.

Similarly, in Japan, Shinto shrines are often found within sacred forests known as Chinju no mori, and are associated with a reverence for and connection with nature. Though some of the animistic beliefs attributed to Shinto have been lost over the past few centuries, the tradition is nonetheless rooted in a belief that gods inhabit and hold special connection with certain types of large and ancient trees.

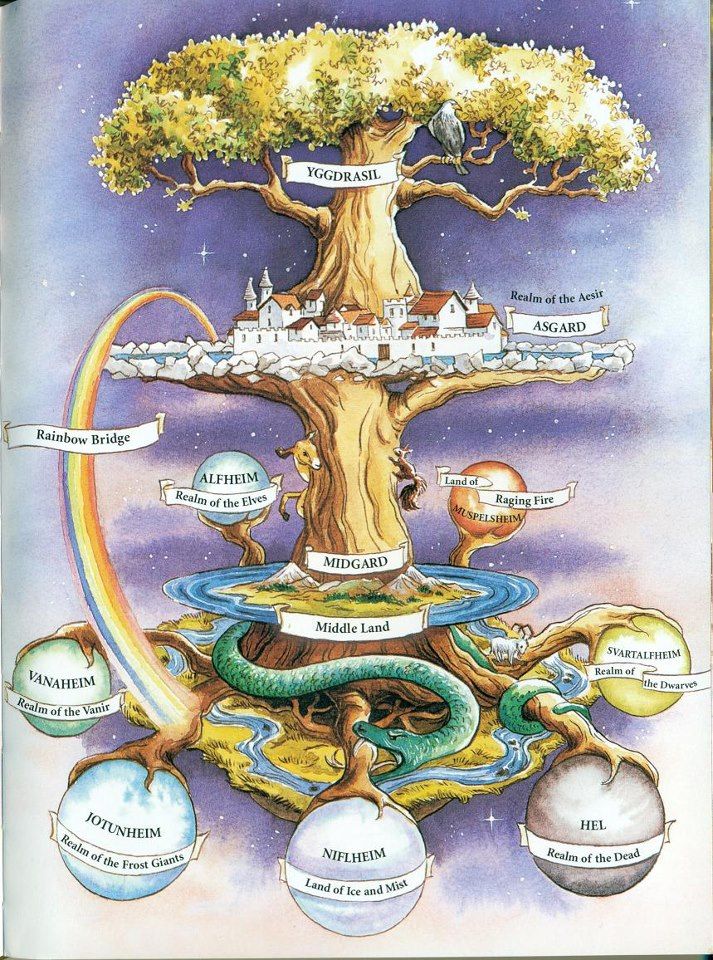

In Norse mythology, which many contemporary Pagans draw on for their practices today, trees are respected and venerated. Yggdrasil, the Tree of Life, is believed to be that which connects the nine realms, linking humans, the gods, and the dead, and is therefore strongly associated with the divine. Yggdrasil, thought to be situated in the middle of Asgard, is a symbol of interconnectedness, wisdom, suffering and eternity.

Personally, I don’t yet know very much about Norse mythology (except what I’ve learned from American Gods and Vikings!) but it’s definitely an area that I’m interested in exploring further—particularly in terms of its connection to sacred trees.

As Cecil Konijnendijk points out, forests are particularly inspiring and meaningful aspects of the spiritual landscape, and have always been places of imagination, wonder, and reverence in the collective human consciousness.

A spiritual experience is an intuitive and emotional kind of experience in which a person feels caught up and carried along—or alternatively, filled and inspired—by a feeling, an idea, an image, or a creative impulse. This can be through religious rituals and disciplines, but also through contact with forests or other parts of the environment”

Cecil Konijnendijk, The Forest and the City: The Cultural Landscape of Urban Woodland

Sacred Trees in Celtic Ireland

Possibly because I have family roots in Ireland, and partially because I think it’s one of the most incredible places I’ve ever had the privilege of visiting, I have a particular fascination with Celtic Irish Paganism, and the incredible (yet tragic) history of the connection between trees and Celtic spirituality.

According to pollen records, the first trees in Ireland appeared around 14,000-12,000 years ago, 4,000 years after the last Ice Age. The pioneer species was the birch tree, followed by hazel, oak, pine and elm, with other species such as ash, beech, maple, and willow coming years later. The first notable phase in the relationships between humans and trees in Ireland began around 800 BCE, with what we might call the “tree veneration” of the Celtic settlers. As these Celts would have been animists, they likely believed all of nature to be sacred, with things like trees, mountains, rocks, streams, and other elements of the environment thought to have their own spirit or numen.

Trees in particular were of special significance to the Celts, and were featured prominently in the language, laws, and customs of the Druids—a high-ranking class among the Celts. Oak is known to have been especially important to the Druids, and it has been speculated that the word “druid” comes from druwid, meaning oak-wise. Mistletoe, which grows on oak, was highly sacred to these ancient people, and was used as a cure-all for a variety of ailments.

In Celtic lore, it was believed that trees could be home to deities, faeiries, and demons, and could house the souls of people who had been buried near them. Faeiries were thought to live in the hollows of trees, referred to as “fairy doors,” and it was thought that by touching these, one could experience potent healing magic, or perhaps even discover a portal to another world.

Because the Celts believed that the trees could house deities, or that they could even be deities themselves, the Druids had very strict regulations about trees. In the ancient Brehnon laws of the Druids, it was stated that doing injury to a tree was akin to doing injury to the gods, and perpetrators could be brutally punished for felling or harming a tree in any way, even sentenced to death for it.

For the Celts, sacred groves were akin to temples, and were thus places of immense spiritual power deserving of respect and reverence.

The tree, like the human, is a mediator between the upper and lower worlds, linking with its serpentine watercourses the underworld of the ground, the surface of the ground, upon which we live, and the sky and air. Thus, the tree is an image of the cosmic axis, a physical manifestation of the maxim ‘as above, so below’.”

Nigel Pennick, Celtic Sacred Landscapes

Ogham

Nowhere is the importance of trees in ancient Ireland as evident as it is in the Ogham script, the earliest known form of Irish writing, thought to have emerged somewhere between the 1st century BCE and 3rd century CE. The alphabet is based on 15 species of trees found in the area, with each of the letters named after a different tree prominent in ancient folklore. In Celtic mythology, the script was thought to have been created by Ogma, the God of eloquence and literacy.

The language was likely used by the Druids for record keeping, divination and magic, as well as to write down stories and folk tales. Though there are traces of Ogham found throughout Scotland and Wales, the majority of it has been found in Ireland, particularly within County Kerry.

The fact that this written language was based on trees, as well as their prominence in folklore, goes to show just how important forests and trees were in all aspects of Irish pagan life. Unfortunately, however, what remains of these traditions today is but a small fraction of what once would have been, as much of this ancient knowledge was lost with the onset of Christianity and the systematic eradication of Druidic culture.

Deforestation in Ireland

Although there is some dispute among historians, it is generally agreed that the first major wave of deforestation in Ireland began with the arrival of Norman and English settlers, and the introduction of agricultural farming practices. This deforestation continued over the course of the next few centuries with the rapid expansion of the population and an increasing need for food and fuel, accelerating even further in the 16th century with the country’s colonization by the British.

With this first wave of deforestation in the 12th and 13th centuries, many of the sacred groves and trees of the Celtic people were destroyed, and with them, many of their associated traditions, spiritual practices, and stories, all of which would have been considered “primitive” by Judeo-Christian standards.

As Marjan Shokouhi notes in ger overview of the history of Irish woodlands, English settlers in Ireland believed that by “taming” the wild wooded land they could also tame the “uncivilized barbarians” who inhabited it, for “cultivating the land was not only to put the soil to ‘good use,’ but to bring the so-called ‘savage nation’ under control and civilize them” (2019, p. 23). Here, we can see how Christians attempted to dominate both the land and the people within it. Even the term “savage” is derived from sylva, Latin for wood, which associates the natives and their lands with barbarianism. From the Judeo-Christain, colonizing perspective, nature was something to be controlled, dominated, and tamed, as were the pagans associated with it.

Moreover, as Shokouhi points out, this colonized/colonizer binary brought on by Christian domination gives rise to nature/culture binaries that sought to create a wide gap between humans and nature where before, there had been none. In doing so, spirit was disconnected from the land, dislocating people not only from their homes, but from their places of dwelling and ultimately, belonging.

As such, through processes of deforestation, it was not only the trees themselves that were lost, but the knowledge they contained, the stories they inspired, and the ways of life that they fostered.

Whereas pre-Christian Ireland was covered in lush emerald forests, today, Ireland’s forest cover is only around 11%—the lowest in Europe—with only 1% of its ancient woodlands remaining.

Though there are ongoing reforestation projects in Ireland today, most of this is centred around timber and capitalistic gain—a profit-driven framework that ignores the cultural, social and spiritual dimensions of trees that are such an important part of the country’s heritage.

Contemporary Paganism and Connections to the Past

So, why do I bring this bit of Irish history up here? A few reasons.

First, to reflect a little bit on how identity and spiritualty can be so deeply intertwined with the natural landscape, to the point where to destroy one would be to destroy the other. Moreover, this goes to show that there is no ultimate separation between human beings and nature—we are a part of it, as it is a part of us.

Second, I bring up this history in order to return to some of the ideas that I explored in my previous post—namely, the problems that arise from an anthropocentric, or profit-driven understanding of the land, particularly as it is tied up with colonization, capitalism, and Christianity.

Finally, even though I’m not a “Celtic” Pagan, or part of any reclaiming traditions, I nonetheless feel a pretty deep sense of connection to this history. While I know very well that there is no unbroken link between the Pagans of today and the pre-Christian pagans, and recognize that contemporary Paganism is just that—contemporary, I do think that there is something to be said for learning about such histories, and considering the roles they may play in our modern practices and beliefs.

Whether “real” or not, this sense of connection to the ancient past is spiritually meaningful to many modern Pagans. And “real” or otherwise, I strongly believe that it is the experience of this connection that truly matters.

Personally, I enjoy learning about the Celts, their mythology, and their ancient knowledge (what little remains of it), as this understanding ultimately gives rise to a deep sense of interconnectivity. Learning about how the Celts related to and venerated the natural world in turn shapes how I perceive and engage with nature, and as such, my connection with the natural environment also fosters a connection with this pagan past.

That is to say, trees can be portals to the past, connecting us with those whose lives were so intimately intertwined with them.

Knowing the significance that oaks held for the Druids, touching a large oak tree today can have the same kind of power that standing in a Neolithic stone circle might, as these are spaces and material entities that retain the spirit of the past, forever exuding the magic of those who created and venerated them.

As Susan Greenwood notes in The Nature of Magic, for followers of nature spirituality, the traditions of the past are embedded within the landscape, and the land itself is alive with the spirits of place and ancestors, whether taken literally, or (as I do), metaphorically.

Though very little is known about the actual traditions of the ancient Celts, or the full extent of the meanings they gave sacred sites, forests, and trees, for many contemporary Pagans, the interpretation of these sites and symbols are an attempt to revitalize and recreate narratives of the past, so that “in the process landscape is given new meaning” (Greenwood 2005, p. 83)—meaning that arises from the combination of our understanding/imaginings of the past, and our active participation in nature.

Landscapes, forests, sacred groves—these places are not only natural sites, but also deeply cultural and historical, shaped by the many people who came before us.

The landscape tells—or rather is—a story. It enfolds the lives and times of predecessors who, over the generations have moved around in it and played their part in its formation. To perceive the landscape is therefore to carry out an act of remembrance, and remembering is not so much a matter of calling up an internal image, stored in the mind, as of engaging perpetually with the environment that is itself pregnant with the past”

Tim Ingold, “The Temporality of the Landscape”

Even though I live in Canada in the 21st century, greatly separated both spatially and temporally from the ancient Celts, when I walk through the small forest near my apartment, I can nonetheless still feel something of this connection to these pre-Christian peoples through embodied engagement with my surroundings. With heightened senses I can take in the sights and smells around me, run my hands over the rough bark of an old oak tree, and imagine what it would have been like to live in a world where everyone felt the same kind of reverence and power I feel in relation to these beautiful giants.

Although the connection to place was much more potent when I was actually on the land that had once been home to the Celts, during my time living in Scotland and my visits to Ireland, I’ve since found that I can recreate some of this experience through the relationship I have with trees.

Trees, in other words, have an inherent connectivity, wherein engaging with them may be akin to opening up (metaphorical) portals to different times and places, both historical and fantastical.

Indigenous Histories

That said, while trees may be able to connect us to spiritual ancestors or far-away lands through the power of the imagination, it also remains crucial for us to consider the real histories of violence and oppression interwoven throughout the landscapes in which we inhabit.

Just as the Irish landscape was forever altered by British colonization, the North American landscape also bears colonial scars. As a Canadian living in Ontario, I recognize that I am living on stolen land—specifically, on the traditional, unceded territories of the Algonquin nation.

I can overlay my own spiritual beliefs, attitudes, perspectives onto this land on which I live, intertwining some of the Celtic traditions that I fell in love with while living overseas with how I connect to this place that I call home. I can bring imagination, enchantment, and fantasy into the ways in which I move through forests and natural spaces. I can foster relationships with the land that arise out of my own ways of being and knowing—relationships that work for me, as a nature-based Pagan witch.

HOWEVER, I think that it is also vitally important to acknowledge and educate myself on the very real, and very dark history of this landscape. Indigenous peoples have always had very specific ways of relating to the natural world—a core element of their cultures that ongoing colonization efforts threatened (and in some cases, continue to threaten) to completely eradicate.

So what does this mean for how I, a white settler, identify with the land, the trees?

This is a question I continue to ask myself, and one that I find is difficult to find a definitive answer for, beyond educating myself, and standing in solidarity with those who were, and continue to be, affected by this cultural oppression.

I won’t go into this too much here, as I’m in the process of writing an upcoming post on the strained and tenuous relationship between nature spirituality in North America and Indigenous peoples and their traditions, including delving in to issues of cultural appropriation that still run through many Euro-American spiritual communities.

But for now, I think it’s important to note that this is something that we do need to think about when we relate to aspects of the natural landscape—to think critically not only about our own beliefs and practices and where they come from, but also the history of the land that we draw power and inspiration from, and who may have previously inhabited these spaces we now deem sacred to ourselves.

To Speak for the Trees

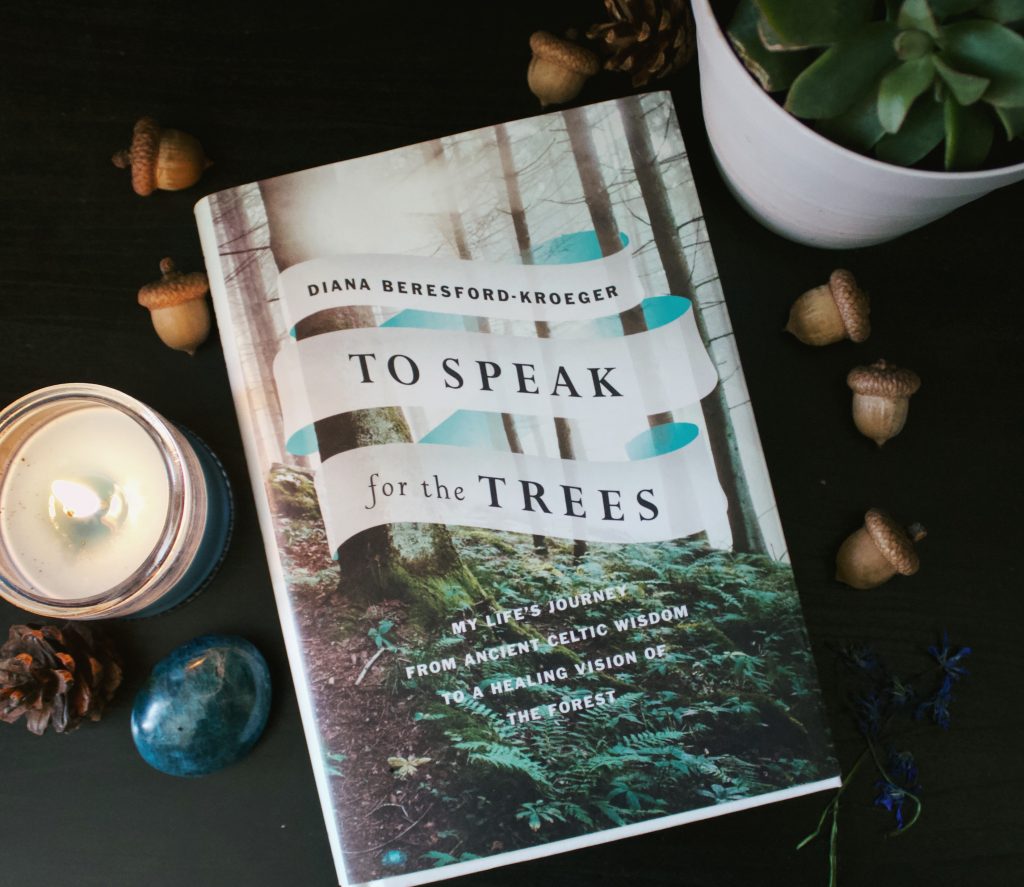

Finally, though I know I’ve already gone on long enough here, I really feel that I post on nature spirituality, trees, and Irish Celtic wisdom wouldn’t be complete without at least briefly looking at Diana Beresford-Kroeger’s fantastic book To Speak for the Trees: My Life’s Journey From Ancient Celtic Wisdom to a Healing Vision of the Forest. I highly, highly recommend this book to anyone interested in Celtic traditions and/or the science of trees. As a Pagan spiritual seeker who tends to lean towards naturalism (and skepticism!), this book really resonated with me.

Part memoire, To Speak for the Trees is about world-renown botanist/medical biochemist Diana Beresford-Kroeger’s life-long love of trees, and her journey to combine scientific knowledge with ancient Druidic wisdom in order to address the ecological crises currently facing our planet.

Beresford-Kroeger spent much of her childhood in Ireland learning about ancient Brehnon traditions and their plant lore, gaining considerable knowledge about the natural world. This fascination with nature, and with trees in particular, lead Beresford-Kroeger to an academic career as a botanist and medical biochemist. However, rather than leaving behind the spiritual knowledge of the Druids that was passed on to her, she takes this ancient wisdom with her through her scientific training, and finds that much of what she learns in university reinforces (rather than contradicts) these Druidic teachings. As such, she discovers that spirituality and science are not antithetical to one another, but rather, compliment each other, and that the best way forward is a holistic approach that draws from and intertwines both paradigms.

In particular, Beresford-Kroeger comes to realize that the scientific knowledge she gains through her research, her fieldwork, and her time in the lab affirms the ancient understanding that nature is the sacred source of all life—that it is everything we need to sustain ourselves. As such, many of her scientific discoveries are also spiritual revelations—the more empirical information she gains about the world, the more convinced she becomes of its sacred nature and inherent divinity.

One of these such scientific/spiritual revelations comes in the form of the bioplan—a concept Beresford-Kroeger sees as a blueprint for the interconnectivity of all of nature, and that attempts to show how by planting more trees native to the areas in which we live, we can slow global warming and prevent climate catastrophe. As she writes, the bioplan is:

“the web, both seen and unseen, that ties the willow to the sapsucker to the butterfly to the ichneumon wasp—and ties all of them to us. It is the evolutionary framework, the balance, the give-and-take-and-give, that allows life to exist and thrive on our planet. Bioplanning is the act of aiding and encouraging the bioplan. In a garden or on a farm, that means realigning the garden to encourage its use as a natural habitat. Seeing for the first time how the whole of the farm meshed into a single bioplan was a sacred experience. The fundamental truth of nature exists around us at all times.” (p. 157)

Seeing and genuinely understanding this interconnectivity underlying the entirety of the natural world is for Beresford-Kroeger based in both science and spirituality. There is for her, and for me as well, no ultimate distinction between these two modes of perceiving the world. And this—this way of challenging the opposition between spirituality and science, and recognizing the sacred nature of the world—this is a place where a lot of my own Paganism and spiritual beliefs stem from. Like Beresford-Kroeger, I am both scientifically-minded (although nowhere near as knowledgeable as her!) and fascinated by ancient Celtic traditions and wisdom. And that is, in the end, completely fine, because these perspectives do not have to be mutually exclusive!

“There is a deity in nature that we all understand. When you walk into a forest—great or small—you enter it in one state and emerge from it calmer. You have that cathedral feeling and you’re never the same again. You come out of there and you know something big has happened to you. Science allows us to explain a part of that sacred experience. We now know that the alpha- and beta-pinenes produced by the forest actually do uplift your mood and affect your brain through your immune system. That pinene released by the trees into the air is absorbed into your body. It tightens you as a unit and makes you reverent towards what you’re seeing. Simply walking into a forest is a holiday for your mind and soul, allowing your imagination and creativity to bloom. I think that is a miracle, and there are so many other miracles of the natural world left for us to discover. We will feel the joy of those miracles. We will save the forests and our planet. The trees are telling us how to do just that—all we have to do is listen and remember.”

Conservation and Spirituality

Finally, To Speak for the Trees is not just a memoire, but also a challenge to all of us to become more aware of this underlying interconnectivity of the natural world, suggesting that taking a spiritual approach to nature (whatever that might look like) is of utmost importance if we genuinely hope to conserve it, and save our planet.

Similarly, as Haydn Washington writes:

Conservation is (and must be), at its core, a spiritual act”

Haydn Washington, A Sense of Wonder Towards Nature, p.183

What Beresford-Kroeger and Washington mean when they say that conservation must be spiritual is not that anyone who hopes to participate in environmentalist action must become Pagan or adopt any other religious beliefs. Rather, they’re saying that if we genuinely hope to protect this magnificent planet, it cannot come from a desire for profit, or a mere sense of obligation. Instead, it must come from an understanding of the interconnectedness of the Earth, and the recognition that nature is sacred by virtue of the fact that it has intrinsic value, regardless of what it can provide us with.

In other words, genuine conservation efforts cannot come from an anthropocentric stance—we must move towards fostering ecocentric perspectives and relationships with the natural world that decentre human beings, and dismantle the hierarchies that keep us at the top.

Anyways, I apologize for this super long post, but I just have a lot to say on this topic! Thanks for reading (especially if you made it through the whole thing!), and as always, I hope you’re staying safe and healthy.

References & Other Resources

Beresford-Kroeger, Diana. 2019. To Speak for the Trees: My Life’s Journey from Ancient Celtic Wisdom to a Healing Vision of the Forest. Random House Canada.

Everett, Nigel. 2015. The Woods of Ireland: A History, 700-1800. Four Courts Press.

Greenwood, Susan. The Nature of Magic: An Anthropology of Consciousness. Bloomsbury, 2005.

Harrison, Paul. Elements of Pantheism: A Spirituality of Nature and the Universe (Third Edition), 2013 (1999).

Irvine, Katherine N., Dusty Hoesly, Rebecca Bell-Williams, and Sara L. Warber (eds.). “Biodiversity and Spiritual Well-Being.” In Biodiversity and Health in the Face of Climate Change, 213-250. Springer Open, 2019.

Jones, Owain. “Materiality and Identity – Forests, Trees and Senses of Belonging.” In New Perspectives on People and Forests, Eva Ritter and Dainis Dauksta (eds.), Springer Netherlands, 2011.

Konijnendijk, Cecil C. The Forest and the City: The Cultural Landscape of Urban Woodland. Springer, 2008.

O’Hanlon, Richard. “Forestry in Ireland: the Reforestation of a Deforested Country.” The Forestry Source, 7, 2012.

Shokouhi, Marjan. “Despirited Forests, Deorested Landscapes: The Historical Loss of Irish Woodlands.” Etudes Irlandaises 44(1), pp. 17-30, 2019.

Varner, Gary R. The Mythic Forest, the Green Man and The Spirit of Nature: The Re-Emergence of the Spirit of Nature from Ancient Times into Modern Society. New York: Algora Publishing, 2006.

Washington, Haydn. A Sense of Wonder Towards Nature: Healing the Planet Through Belonging. London: Routledge, 2019.

Williams, Kathryn and Harvey, David. “Transcendent Experiences in Forest Environments.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 21(1), pp. 249-260, 2001.